Do you manage an infrequent product? How do you know you have a product-market fit?

The concept of product-market fit is blurry and suffers from a clear definition for low-frequency products. We will explore ways to draw a line in the sand while measuring product-market fit.

Managing and growing a business centered on an infrequent product can be an enormous challenge, as I learned over the past dozen years of my career. My experiences inspired me to begin writing this blog and share my insights. Infrequent products are often treated as a “bug” as opposed to a “feature,” but they shouldn’t be.

The concept of infrequent product and product-market-fit

So what exactly is an “infrequent product”? The term can sound a bit like jargon. Simply put, it is a product in which user transactions occur less frequently than once in three months. Examples of infrequent products include Booking.com. Zillow, Etsy, Warby Parker, and other likes.

In this blog, we will explore the concept of product-market fit for an infrequent product and an approach to measure it. Before that let us understand the concept of product-market fit and why it is essential?

If you consider industries on a spectrum, personalized medicine or biotech companies, they predominantly flirt with invention risk - the risk of not bringing the next best medicine into the market. On the other end of the spectrum, the web/mobile apps are primarily about market risk - the risk of not adopting the product by the market is more ominous than any other risk. For instance, rarely do mobile/internet apps invent new technology. They primarily leverage the existing tech to deliver value to the customers.

Assessing product-market fit serves as a traffic light signal to indicate the degree to which the market adoption risk exists. In other words, it demonstrates how much does the market really desires the product. Product-market fit happens when the customers perform the core behavior that helps them gain value. In the case of a frequent product like WhatsApp - the core behavior revolves around messages (reading/sending) whereas, in the case of an infrequent product like Airbnb, the core behavior is booking a place to stay.

Product-market fit happens when the customers perform the core behavior that helps them gain value.

Assessment of product-market fit

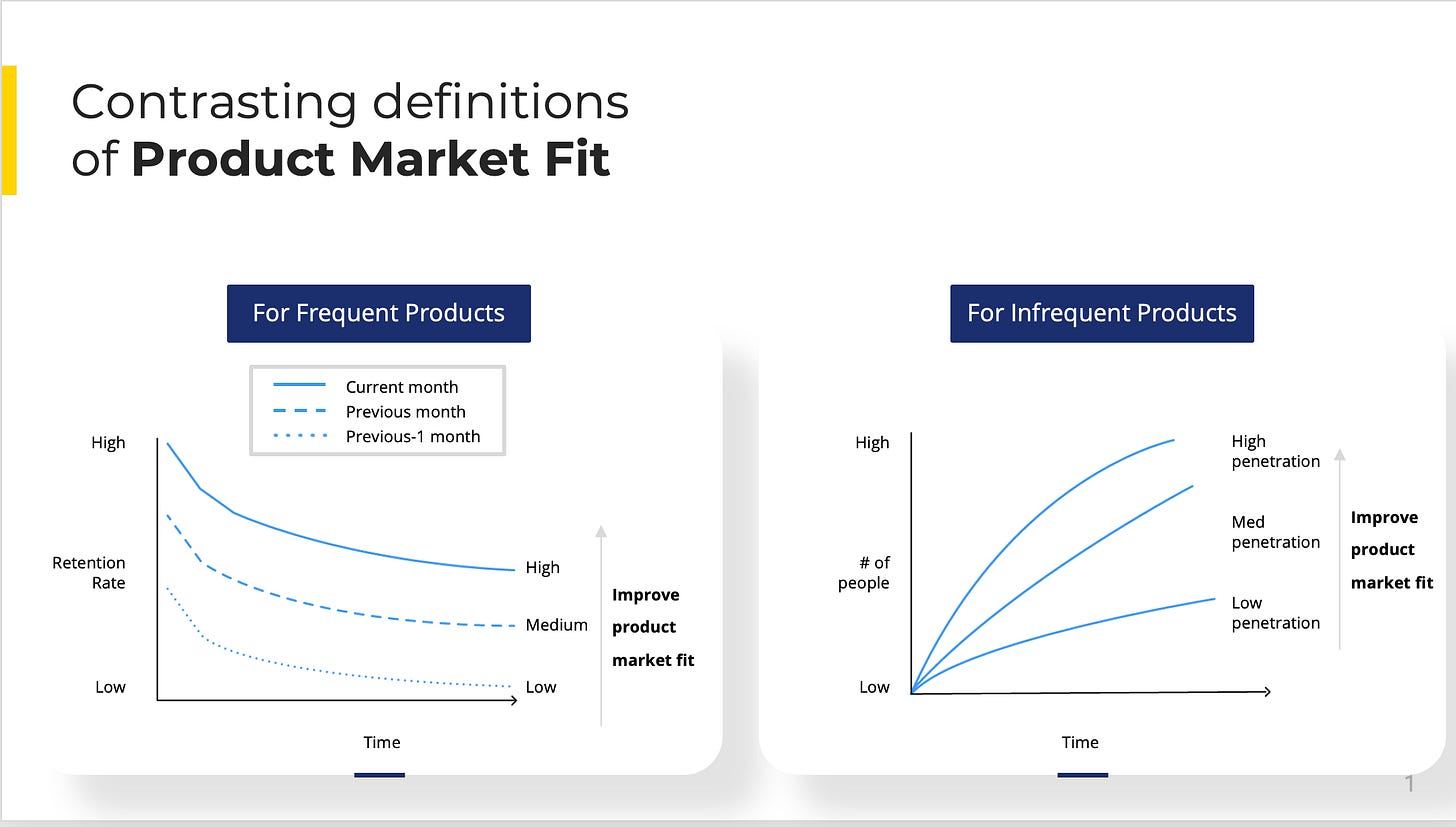

In a frequent product, the way to assess product-market fit is to check what is impeding the users from periodically repeating their core behavior and then remove those aspects causing friction to ensure that more users are retained to perform this core behavior. The higher the retained users, the greater it signals product-market fit for a frequent product.

For an infrequent product, the nature of the business is highly transactional – as a result, a customer may not be retained, as a customer might be with a “frequent product.” But understanding and meeting your market’s needs and demands – or product-market fit – is every bit as important, and the number of core transactions becomes the measure of success. The core transaction is the cornerstone activity that accrues value to the customer when performed.

Consider the earlier example of Airbnb - the more customers book nights to stay (the core transaction); we could argue that more Airbnb is appealing to the market and fitting their requirements. Thence the greater the number of core transactions, the greater the product-market fit. Incidentally more product-market fit also means more market penetration.

Since retention doesn’t apply for an infrequent product, the measure of product-market fit is that of increasing the number of transactions i.e., market penetration.

To fully understand product-market fit, it’s necessary to understand the nature of infrequent products. They are essentially utility products. All of them solve a pain point that happens episodically to customers. Examples include:

Expedia - solves the problem of finding the right flight/hotel to travel; transaction refers to the number of travel bookings.

Zillow - solves the problem of finding a property; transaction refers to the number of leads generated.

Indeed - solves the problem of finding a job; transaction refers to the number of jobs submitted.

Consider a physical analogy

Utility products – things that we need and purchase, like furniture, eyewear, cars, shoes – by nature often have a brick-and-mortar presence. But how does this connect to an infrequent product? I began thinking about a concept coined by D’Arcy Coolican called the “despite test,” in which people are using a product despite it not being the best thing out there, or even that it’s terrible; this reflects that it’s wanted and not just needed. Well, I have hardly seen an infrequent product that doesn’t pass what I like to call the “despite digital test,” meaning the product or service is already being successfully sold and consumed in the non-digital, offline world in a physical business.

“despite digital test,” meaning the product or service is already being successfully sold and consumed in the non-digital, offline world in a physical business.

Take the example of travel. Expedia started at a time when there were travel agencies such as Thomas Cook was already present and thriving. Travelers who sought guidance approached the local travel agencies before the birth of Expedia (or similar such online travel agencies). Travel products like Expedia passed the ”despite digital test” and successfully transitioned to the digital world. Eventually, Expedia unleashed the power of the internet to grow the products worldwide.

If a product passes the “despite digital test,” i.e., a physical business already exists, how does this help measure an infrequent product’s market fit?

The blurry concept of product-market fit

While the concept of product-market fit is powerful, it is also unclear in terms of the precision of the definition. I have sat through meetings wondering how do I know whether a product has achieved its market fit. Is there a threshold at which point we could say that the product fits the market? For instance, if you are selling a tax software product, have you achieved the product-market fit at 100 transactions, 1,000 transactions, or 10,000 transactions? How do you know?

So let’s play this out – consider a tax software that is getting built from scratch in, let’s say, Australia, and assume there is no dominant tax software as yet. How do we assess the product-market fit (PMF)?

One way to do this is to go back to the roots of how businesses have been managed and grown for ages. We would launch a physical business in one location, prove that it could make money (product-market fit), and then scale it across various locations or expand the distribution (growth).

Extending the concept to a digital product should be no different. Going back to our tax software example, you can define the “initial product-market fit” by benchmarking with the revenue of the best-chartered accountant agency in a location, say Sydney in Australia.

Going back to our tax software example, you can define the “initial product-market fit” by benchmarking with the revenue of the best-chartered accountant agency in a location, say Sydney in Australia

You can choose the location for your business by taking this approach:

Availability of early adopters: Pick a location where you can target your early adopters. In the above example, let’s assume a big city like Sydney is where you will find many people interested in using a type of software to help do their taxes.

Choice of the hierarchy of location involves judgment: Whether you want to choose a city, district, or county is up to your discretion. The principle is to start small and expand.

The thought of using a physical business to gauge the success of a digital product may be unsettling and not easy to digest. But looking at the concept of “true product-market fit” might help.

Unlike a physical business, operating on the internet has zero marginal costs and zero distribution costs. In the above example, if you were to expand your physical tax store, which had been successful in one location, you would open more stores across the next set of locations. The more success in those other locations, the better your product would fit with the market. However, having more physical locations does equal higher costs – for store setup, employees, et cetera.

Digital businesses benefit from expanding without incurring any such costs (zero distribution costs). So, upon achieving the initial product-market fit, the product can penetrate the market by setting goals catering to your ambitions. The phase after an initial product-market fit that signals increased penetration (transcending locations and customer segments) is called the “true product-market-fit.”

The phase after an initial product-market fit that signals increased penetration (transcending locations and customer segments) is called the “true product-market-fit.”

What if the industry has already gone digital?

In some cases, like travel, the industry is mainly digital. So how does initial product-market fit even apply here? Consider a digital travel company (not the leader in the category) and apply the location filter through SimilarWeb (SW) or any other suitable software. Benchmark at the appropriate location level to understand the data. The data is more proxy than real. For instance, SW will provide the traffic details, and then you may have to arrive at the total conversion for that location.

I suggest that you not consider the leader in the industry for benchmarking because it may be hard to beat the leading company’s record when you are starting. The category leader likely benefited from the duration of existence, a brand name that leads to organic traffic, and other advantages.

I suggest that you not consider the leader in the industry for benchmarking because it may be hard to beat the leading company’s record when you are starting.

So, in summary, the initial product-market fit can be benchmarked in two ways – with the relevant physical business, if the industry has not gone entirely online, or by using the progress of a non-leading digital company, if an industry has gone completely digital.

How long does it take to achieve an initial product-market fit?

The time to achieve initial product-market fit is mainly dependent on the nature of the category. A peer-to-peer payment app can make it happen faster than high-value jewelry e-commerce.

Of course, it is not foolproof.

Comparing offline and physical businesses have its challenges. In particular, you may not get the relevant data for a couple of reasons:

Some categories like metasearch engines (Kayak or Wego) may not be easy to benchmark and settle for proxy data.

Industries that have gone digital are hard to compare if the traffic predominantly flows to the app.

Infrequent products are hard to manage but not impossible to manage. They are, in essence, utility products that people need access to, so to achieve success, it’s a matter of taking cues from brick-and-mortar businesses and understanding how and where your product fits best.

Do share your views on this thought experiment in the comments section.

I plan on sharing my thoughts about infrequent products once a month. Consider subscribing if you haven’t already.

I loved you view on infrequent product. I like the point of "All infrequent products are Utility Products and not the other way round".

I wanted to know you opinion on how ICED theory perceived on PULL vs PUSH product.

or Can ICED theory be used on entertainment products?

This is a very important thought and action piece to add to the product/market fit conversation, and ultimately a viable business model. If I have a product and people don't use it that often, how successful will I really be? How can I build a 'story' that is compelling and convincing to investors, etc? Great food for thought. I especially like the focus of control over the user experience - address as many aspects as possible to delight me, the customer - and I will look for ways to use your product! www.CustomerDiscoveryPros.com @GrowWithRandy